Our Story

The history of Bike New York is the history of the Five Boro Bike Tour, and it all started with an audacious plan to take a group of high schoolers on a ride across New York City.

New York City, February 1977: It was too cold to bike, but not cold enough to keep us from dreaming about warm summer rides through the streets and parks of New York City. Little did we know that these little dreams would coalesce in a matter of months to become a reality—a very big reality—that would live on for decades.

For years, American Youth Hostels (AYH) had been encouraging people to cycle; back then, young travelers often journeyed from hostel to hostel on foot or bike. One of the leaders of AYH’s Bicycle Committee, Sal Cirami, worked for the NYC Board of Education’s school lunch programs. By chance, Sal met Eric Prager, whom the Board had recently commissioned to develop a bicycle safety program. A brief conversation resulted in Sal inviting Eric to the next monthly Bicycle Committee meeting. Eric outlined his plans for his bicycle safety program at that February meeting.

That program comprised clinics on bike safety and repair, and would culminate in a day trip around the five boroughs to allow the students to practice what they’d learned. Thus the Five Boro Challenge was born. Unlike most recreational rides at the time (which took place in the countryside), this one would explore and celebrate the urban landscape.

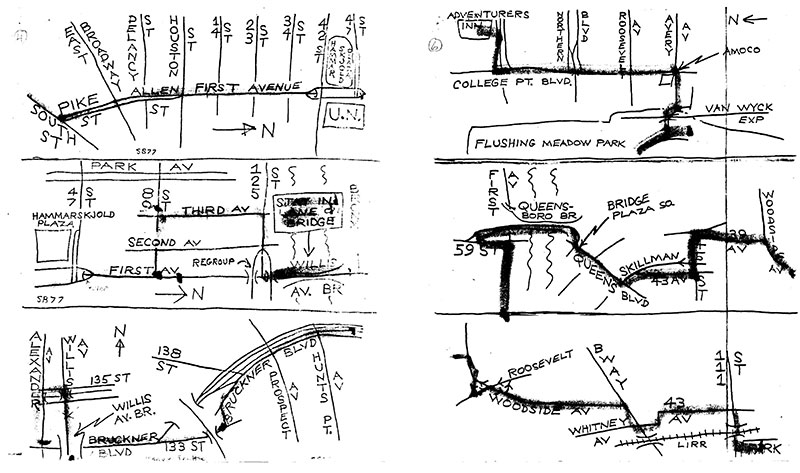

About 50 high school students from five schools and 200 members of bicycle clubs were set to participate. (Why should the students get to have all the fun?) The 50-mile ride would begin and end in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, and wind south through Brooklyn, over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge into Staten Island, and then, after a quick ferry trip, up through Manhattan, into the Bronx, and over the Throgs Neck Bridge back into Queens.

The night before the Challenge, a group of eight or nine ride leaders slept on the floor of a fellow leader’s apartment. At 6:00AM on Sunday, June 10, they rode over to the Unisphere in Flushing Meadows to check in the 250 cyclists. There was no entry fee, and only one sponsor: Nathan’s gave out hot dogs and soda in the the Bronx at the ride’s one and only rest stop.

The route was not closed to traffic as it is today, but we did have two police escort vehicles at the front and back of the pack. Nevertheless, after a few miles it became clear that something had to be done to ensure that the group could stay together; moving 250 cyclists through an intersection during a single green phase was impossible. So the NYPD decided to bend the rules a bit and allow the ride leaders to block traffic at cross streets so the group would remain intact.

Soon after the Tour, Ellen Farrant committed her experience to paper. Her remembrance of the Manhattan portion of the route reads as if it could’ve been written last year; the only thing missing today is the Fulton Fish Market:

“In Manhattan, we passed the South Street Seaport with its four-mast schooners in port, the Fulton Fish Market with its unforgettable aromas, Chinatown, some Bowery personalities, the beautiful brownstones, and of course, always in the background, the tall buildings. We were travelling along First Avenue. At first, there were many apartment houses and then we went into older sections with lots of stores selling everything you could think of. There were apartments over these stores and people were looking at us. It was the attitude of these people which made me the ride a delight to me. If the boroughs were different, the people were the same. They were hanging out of windows, coming out of stores to line the streets. Some were cheering, some were staring. The kids were dancing up and down and running alongside us. Those who had bikes rode with us for a while. To see people smiling and cheering really made us feel fantastic. We knew we were doing something special, but the attitude of the people just enforced it more.”

At the end of the day, we were exhausted and elated, and we figured that was that. None of us thought we’d be riding again next year—much less the year after that, and the year after that, and….

When Ed Koch became mayor in 1978, his administration sought ways to promote bicycling. Charlie McCorkle of Bicycle Habitat and Transportation Alternatives, along with the AYH group and leaders of other New York cycling organizations, took the Five Boro Challenge idea to City Hall. The mayor’s office loved it, but the word “Challenge” made the Tour sound too difficult for a family-friendly ride, and the mileage had to be reduced to make it more accessible. After three hours of brainstorming, the committee landed on the “Five Boro Bike Tour,” and shortened the route to 40 miles.

Along with the mayor’s blessing, we enjoyed the support of agencies like the Emergency Medical Services and the New York City Fire Department. The Department of Transportation coordinated the involvement of City agencies and worked with the NYPD to make the route traffic-free. They used the leapfrog system, with waiting points about 40 blocks apart so they wouldn’t have to close the entire route down to traffic all at once. The police blocked traffic for the first 40 blocks, then held us there while they leapfrogged ahead to close the next section to traffic.

The City requested that the Tour be limited to 2,500 cyclists, but we ended up with 3,000. In a single year, the ride had grown by more than 1000%. Changes to the route took riders on highways for the first time in New York’s history, and necessitated making a U-turn in Staten Island. Not surprisingly, 3,000 cyclists trying to make a U-turn caused quite a traffic jam and drew numerous spectators—one of whom would change the course of the Tour forever. The vice president of community services for Citibank turned out to watch the spectacle, and resolved right then and there that Citibank needed to be involved. That Monday, he met with his colleagues, and Citibank became the title sponsor of the Tour for the next 11 years.

At the end of the ride, the assistant police chief inspector said, “If we do this enough, we’ll get it right.” We took this as a good sign.

In 1980, subway workers went on strike a month before the Tour. AYH set up a phone bank to answer questions about cycling as an alternative means of commuting to and from work, and, along with Transportation Alternatives, set up cones and bike route signs on New York City streets. Soon enough, the City got on board: Mayor Koch held a press conference and described how Beijing residents used bicycles as their preferred way to get around, and suggested that New Yorkers try doing the same during the strike. And they did—en masse. Bicycle sales soared, New York City suddenly became a city of cyclists, and the Five Boro Bike Tour was the thing to do. That year 12,000 people signed up.

Planning the ride soon became a full-time job for a small staff, and attendance ballooned to upwards of 32,000. City officials decided the party had gotten big enough, and Bike New York has capped it at that number ever since. In 1999, AYH concluded that the Tour needed more attention and spun itself off as two independent non-profit entities: Bike New York, to run the Tour, and the Five Borough Bike Club, which in addition to organizing day and weekend trips, supports their much-grown sibling by providing volunteers and technical expertise. Bike New York (est. 2000) has since developed other rides and, in the tradition of the first Five Boro Challenge, a robust and free bike education program. These educational offerings are funded in part by proceeds from Bike New York events. Since 2007, we’ve taught bike skills to more than 100,000 kids and adults throughout New York City.

Each year, on the first Sunday in May, we’re thrilled to welcome 32,000 riders from every state in the nation and 65 countries around the world for an experience of the Big Apple unlike any other. It’s a chance for the global cycling community to come together to grab life by the handlebars and ride for a reason.